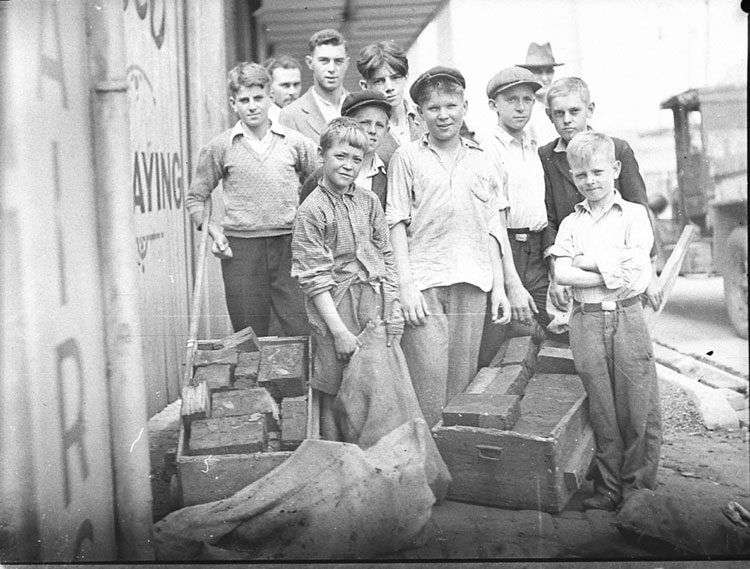

I would like to set the record straight about this picture of young boys taken by Sydney photographer Sam Hood in the 1930s. It is one of a set of three in the collection of the State Library of New South Wales all of which have been titled by the Library ‘Block boys at St Peters’. Because the boys are handling wood blocks, perhaps the label was originally written as some kind of pun, but it is entirely misleading. These are not block boys. That term belongs to another class of Sydney youths and I will come to them later.

The unfortunate labelling of this picture has been repeated by other cultural institutions (here and here, for example) and has even been expanded into erroneous explanations about what the boys are doing, which have then been broadcast – and not only on internet plagiarists’ sites. I was provoked into writing this blog post after seeing a beautifully mounted blow-up of the picture hanging in The Henson in Marrickville with a credit to the State Library of NSW. Nice addition to the décor but a pity the hotel has been provided with an incorrect description, which states that the boys ‘… are helping to build roads using a method called woodblocking’.

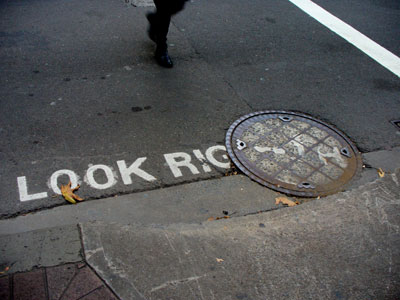

The real story is just as interesting, but without the connotations of child labour. The boys are not constructing a road. They are hanging round with their push carts and hessian bags to collect discarded wood blocks, which they will take home as fuel for the family fire or stove. Wood blocks were once widely used in Sydney for street paving. Until the late 1800s the city’s roads were generally unsealed but the 1890s saw woodblocking come into widespread use by municipal councils, with hardwood blocks steeped in tar being laid like bricks, hammered close together and top-dressed with more tar. But by the early 1930s this method of road building was no longer used and councils started ripping up the worn wood blocks on some roads and replacing them with asphalt or concrete, often in large-scale Depression-era programs that provided employment for out-of-work men.

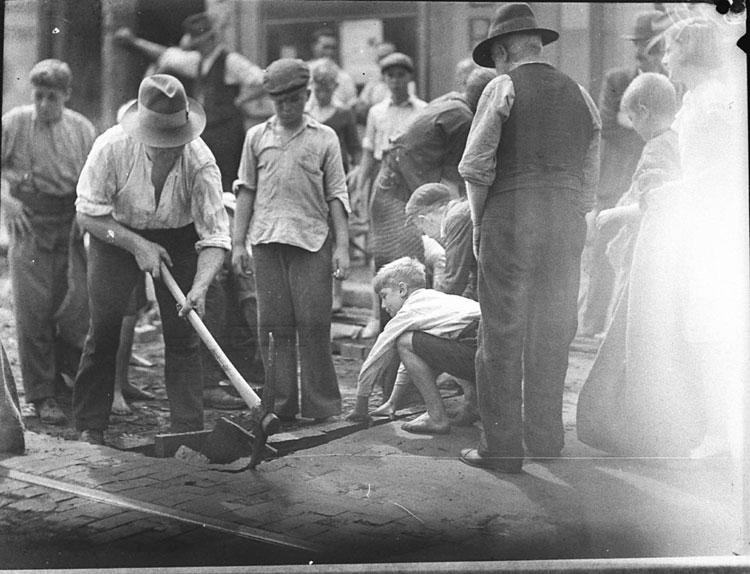

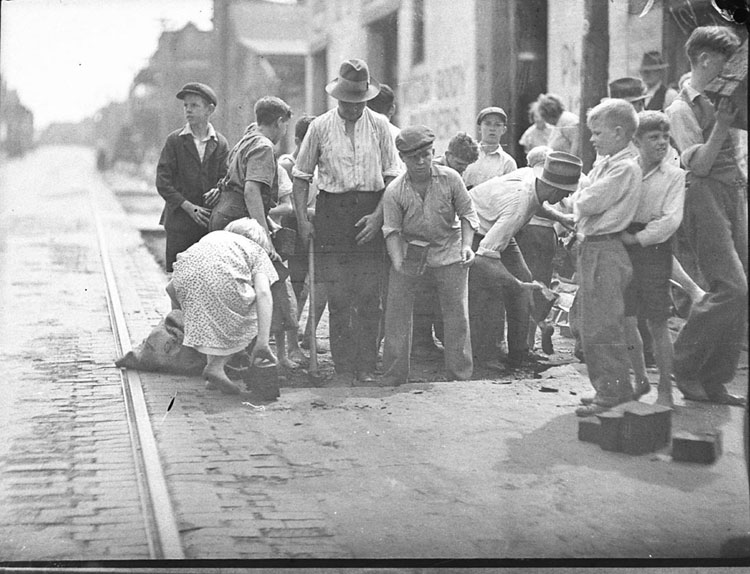

Those tar-impregnated woodblocks would have burnt well. They were prized by householders as free fuel and were quickly purloined as soon as the road workers dug them up. The Sam Hood picture was taken during the hard times of the Great Depression and the local boys are contributing to their families’ wellbeing in a practical way. The two other pictures taken by Hood in St Peters at the same time have been damaged a little, perhaps while the negatives were in storage but, with a bit of staging for the camera, they clearly show what is going on. In both of these there is also a girl collecting blocks alongside the boys.

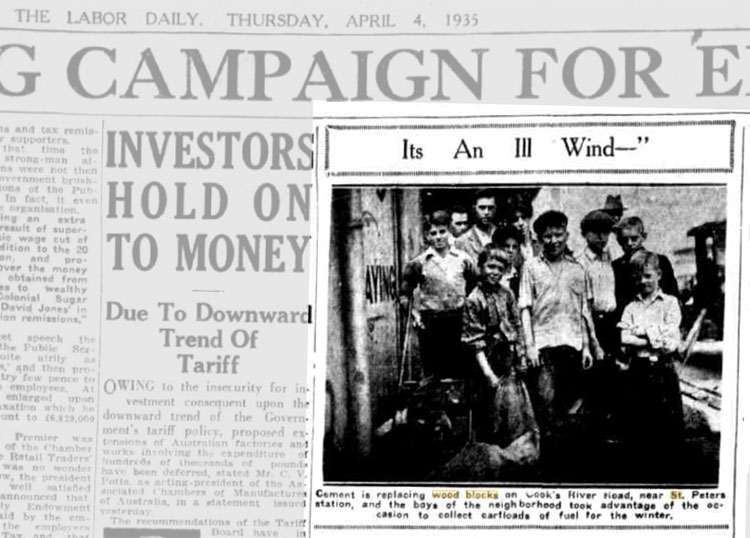

And just to prove my point I searched for and found the photograph in question published in a contemporary newspaper. Sam Hood had his own commercial studio but also took press photographs, working full-time for a while in the 1930s for the Labor Daily. Â On 4th April 1935 that newspaper printed his photo on page 8 under the heading Its an Ill Wind — Â with the caption:

Cement is replacing wood blocks on Cook’s River Road, near St. Peters station, and the boys of the neighbourhood took advantage of the occasion to collect cartloads of fuel for the winter.

St Peters, by the way, is an inner suburb of Sydney and what was Cook’s River Road is now part of the Princes Highway.

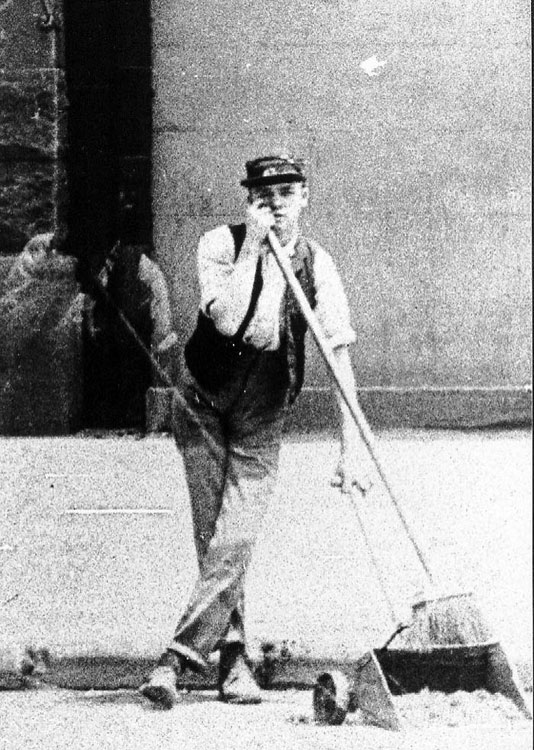

So who were the actual Block Boys? In the early 1900s the City of Sydney employed a small army of youths to sweep up the tons of manure deposited by horses on the city’s streets. Equipped with long-handled brooms and scoops, these block boys, or ‘sparrow starvers’ as they were jokingly called, were each assigned a city block to keep clean. But by the 1930s motorized vehicles were outnumbering horse-drawn vehicles in the city and street cleansing was subsumed into the more generalised duties of Council’s other outdoor workers. The coveted job of block boy was phased out.

Not many photographs were taken specifically of these youths, but they often turn up in photographs taken for other purposes. The picture below is a detail from a photograph in one of the Demolition Books kept at the City of Sydney Archives. The block boy leans on his broom in Sussex Street to watch as the photographer documents the building behind him, which is slated for demolition.

I have a large, framed copy of this picture hanging in my house. Left over from an exhibition at Sydney Town Hall, it was given to me by the city’s archivist some years ago as thanks for a small job I had done. I chose this particular photograph because it is a double exposure. The boy’s doppelganger is lounging beside him.

References:

Davies, Alan, Sydney exposures: through the eyes of Sam Hood and his studio, 1925-1950. Sydney: State Library of New South Wales, 1991.

Fitzgerald, Shirley, Sydney 1842-1992. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1992.

Fitzgerald, Shirley, The sparrow-starvers: block boys 1890-1930, catalogue for an exhibition of documents from the City of Sydney Archives, Sydney Town Hall, June 1997.

Shepherd, Allan M., The story of Petersham 1793-1948, Sydney: The Council of the Municipality of Petersham, 1948.