I am researching the history of a nineteenth century row of houses in Sydney’s inner west. It’s not my usual kind of writing gig but it has been interesting following the money. Wealth accumulated in good times by an enterprising immigrant from Yorkshire, shared with his son as a business partner, lost when the son’s extravagant ventures are caught out by a national financial depression. What’s left is a smattering of properties that have been salvaged for heritage listing by repurposing – gentlemen’s residences divided into flatettes, a wool store fitted out as university outpost campus, a private mansion transformed into a Catholic educational institution.

The buildings are notable for the need these colonial nouveau capitalists had to monogram their possessions. The firm’s name is embossed on the wool store – an understandable commercial imperative. But on the gateposts of the father’s 1860s villa his initials AH are stuccoed in botanical calligraphy so elaborate that they are barely legible.

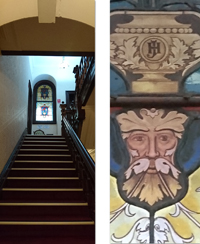

The son’s entwined initials JH in more restrained but authoritative capitals decorate the interior of his opulent 1880s mansion. I can imagine the thrill of self-satisfaction this sleek young mayor experiences as he glimpses the stained glass panel on his way upstairs from the expansive vestibule of his domicile.

Fast forward to the late twentieth century and an upsurge of the monogram for marking property – though more likely someone else’s property or else a piece of public infrastructure. Taggers appropriate territory with marks that are generally illegible except to themselves or to cohorts that matter.

I came across a graffiti supplies website recently, and this comment from a user: ‘ I wrote the name test when i was in high school. I liked it cause every time i saw the word test in a context totally unrelated to graff i creamed a little’.

Here is the thrill of self-affirmation. This graffitist has gone for ordinariness over illegibility for his tag, and finds satisfaction when he sees,  not only the property he has marked,  but every single item where his moniker ‘test’ happens to appear – books, advertisements, notices, school whiteboards. His mind (and his member) believe that all these base are belong to him.

At least what you don’t really own and have not mortgaged will not send you bankrupt.

Images by meganix, taken in 2017 in Sydney: Stanmore, Circular Quay, Newtown and Strathfield.

![Road safety poster using Ian Macmillan’s famous 1969 photograph, issued by the Kolkata [Calcutta] Traffic Police in February 2013.](http://www.meganix.net/pavement/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/BeatlesKolkata_65951375_9358d13f-8536-4294-98c6-2b358c560b1f.jpg)