Today’s guest spotter is Bradley L. Garrett, a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London, where he is studying Urban Exploration. Bradley’s own blog is here.

I have lived in Clapham, in South London, just across the street from Clapham Common (a huge park) for about eight months now and six months ago I bought a bicycle. This was a significant event because it meant that I no longer took the bus to Clapham Junction train station, I now rode my bike through the park every day instead in what I thought to be a small victory over mundanity.

I have lived in Clapham, in South London, just across the street from Clapham Common (a huge park) for about eight months now and six months ago I bought a bicycle. This was a significant event because it meant that I no longer took the bus to Clapham Junction train station, I now rode my bike through the park every day instead in what I thought to be a small victory over mundanity.

The first time I encountered the little freehand graffiti penis was on one such ride. I was listening to an audio lecture by Arnold Weinstein about Baudelaire’s poem The Swan and here comes this phallus, standing erect in the road like a raucous troll, exacting some sort of fare I was sure. But how to pay it? Figuring all it wanted was some attention I photographed it and moved on.

For six months now I have encountered this masculine assemblage, swerving around it at the last second, sure that, like some form of voodoo charm, it would hurt somebody if I ran over it. Sometimes I would remember it before my encounter, anxious to see if it finally had aroused enough offence in the community to have it painted over. Every once and a while I would stop next to it, seemingly not of my own accord, and stare around, wondering what sort of thought or action it was meant to invoke, feeling like someone was watching and noting my confusion with pleasure. One biker stops, check.

It’s almost mathematical in is perfect pointedness. Even the fact that one testicle hangs slightly lower than the other seems to me to be anatomically correct. Thinking that after months of study, I had now understood its form, my analysis of the thing moved on to function more seriously. The phallus points straight down the asphalt path. My first inclination was, of course, to assume that it points the way to something. Perhaps it was the remnant of a petty birthday party joke, a Facebook tagline proclaiming “when you arrive in Clapham Common, follow the penis to Dave’s party.†Later, I began to wonder if the trajectory of the penis was subsidiary to its location. Could it be a meeting point of some sort?

This notion seemed to be reinforced by my mate Mike over drinks one night who proclaimed Clapham Common as a place where gay men go to “get bummed†which in America (where I come from) means to be depressed but here is some euphemism for anal sex. Could it be that this innocuous little sign I swerved around everyday was a meeting point for clandestine homosexual encounters at night? Perhaps one day, I thought to myself, I would conduct a 24-hour stakeout to satisfy my need to unravel this mystery.

Finally last week, wrapped up in sweaters, scarves and gloves, in some strange sociological crisis, I did indeed undertake such a weird experiment. What happened was this: just across from the white penile package, there is a park bench which, if you were to sit on it, positions you perfectly to observe the sign (or encounters with the sign). I sat there on a lazy Sunday, pretending to read a book so that I could view interaction with it. And what I saw disturbed me.

Time after time, whether confronted by pram pushing Mommies, solitary walkers or ambitious runners, no one noticed the phallus. They rolled over it, stepped on it and ran past it without even a glance. Thinking that maybe I had, in some sick vision, just imagined the damn thing, I walked over to it. Still there. And then what I saw gave me the shivers.

A second phallus, just up and to the left, barely visible, but there. Even worse, it was a different colour and facing a different direction! How could I have missed this before? Horribly disturbed by the new revelation, I walked home, sullen, curious as to what kind of ghastly person would sketch a pair of horrors like this, knowing the frustration their presence would invoke.

[Now that Bradley has pointed out this parkland penis in London, the Pavement Graffiti blog site will return to the subject of street wangs from time to time]

Recently uncovered by Marrickville Council during street plumbing activity under two Camphor Laurel trees on the eastern side of upper Metropolitan Road, Enmore, Sydney, are what appear to be sandstone cobblestones.

Recently uncovered by Marrickville Council during street plumbing activity under two Camphor Laurel trees on the eastern side of upper Metropolitan Road, Enmore, Sydney, are what appear to be sandstone cobblestones. Other views suggest the sandstone course may have been associated either with some early civil works project or may have been laid in conjunction with the arrangement of street tree planting.

Other views suggest the sandstone course may have been associated either with some early civil works project or may have been laid in conjunction with the arrangement of street tree planting. I love Lu Xun Park. It’s in Hongkou, Shanghai, and is my most favourite place on earth at the moment. Everything happens here – there is dance, tai chi, singing, talking, and sitting. Lovely, to me, and I can’t even speak Chinese.

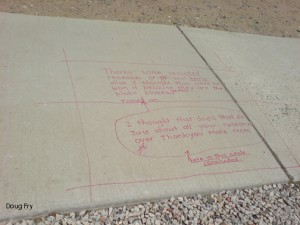

I love Lu Xun Park. It’s in Hongkou, Shanghai, and is my most favourite place on earth at the moment. Everything happens here – there is dance, tai chi, singing, talking, and sitting. Lovely, to me, and I can’t even speak Chinese. Sometimes migrant workers write their story on the ground asking for help. They come to the city from rural areas and often have trouble finding work. The second photograph was taken after rain had blurred a woman’s story about her current living situation.

Sometimes migrant workers write their story on the ground asking for help. They come to the city from rural areas and often have trouble finding work. The second photograph was taken after rain had blurred a woman’s story about her current living situation. Apart from a failed first year university class (and my weekly trash TV fix of Bones) I don’t really have any experience in the field of psychology, so I’m only making a vaguely educated guess when I say that the author/illustrator of this work is probably a paranoid schizophrenic.

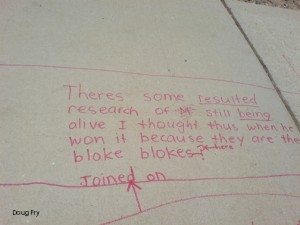

Apart from a failed first year university class (and my weekly trash TV fix of Bones) I don’t really have any experience in the field of psychology, so I’m only making a vaguely educated guess when I say that the author/illustrator of this work is probably a paranoid schizophrenic.