Sometimes graffiti is hidden in secret places, sometimes it is in plain sight but its meaning is hidden.

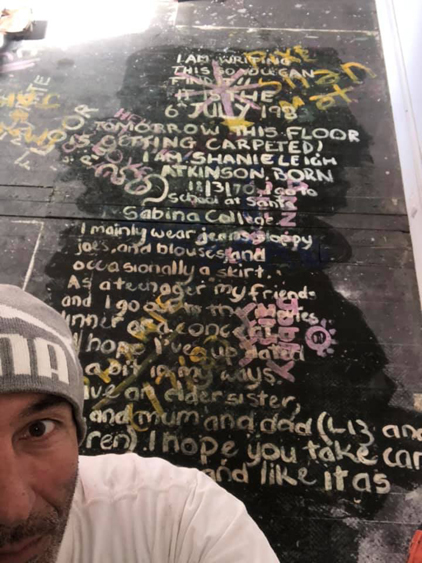

Not so long ago a Sydney builder was surprised when he pulled up an old carpet and found two large messages painted on the floorboards underneath – so surprised that he posted photos of them on his Facebook page.

It’s not all that unusual for renovators and demolishers to find hidden graffiti left by tradespeople at some earlier date in a building’s life. But these personal statements composed by two young sisters in 1983 are extraordinary both for their size and for the detail of their content. They are like secret/not secret teenage diary entries concealed by floor covering. Those girls wanted someone in the future to read all about them, but they could never have anticipated the mediatisation of their words via digital photography and social media.

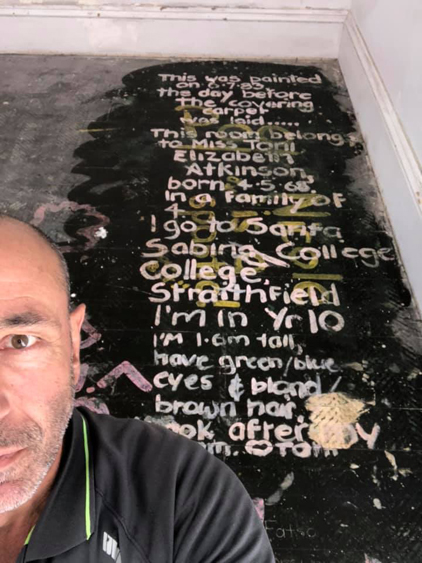

Hidden graffiti can be revealed not only by accident but by determined sleuthing. Researcher Susan A. Phillips, for example, photographed pencil, charcoal, and scratched graffiti hidden under the bridges and in the drains and culverts of Los Angeles. Written mostly by people who were “transient, ethnic minorities, or queer” these marks were up to a century old. Phillips spent over twenty-five years collecting images and stories for her remarkable book The City Beneath.

Phillips remarks on graffiti’s versatility as a clandestine form of expression. The condensed messages she found in hidden places were most often related to the name of someone or something, or were sexual words or drawings. But there was also enigmatic writing and what she called “odd hieroglyphics”.

Odd kinds of graffiti whose meaning is hidden are sometimes referred to as cryptic graffiti. These might be written in secret places, as Phillips’ examples were, but it are just as likely to be easily visible in public places. One practitioner of cryptic graffiti is the Hawaiian artist who rather unimaginatively calls himself Cryptik. This person hand-paints Eastern philosophy iconography on Western walls. His Cryptik Movement “is dedicated to helping humanity evolve towards greater awareness and understanding through public art”. While his walls are aesthetically pleasing they do not represent his philosophy in any obvious way.

A few years ago The Age journalist Tom Cowie wrote about some “cryptic drawings appearing on Melbourne footpaths”. When interviewed, the artist, Astral Nadir, explained that philosophy was his inspiration and that the theme of space and forests was a recurring motif. Nadir called his marks ‘glyphs’ but, curiously, he maintained that his work was not graffiti. I would disagree – of course it is graffiti. But I do agree with the journalist that ‘cryptic’ is an appropriate term to describe Nadir’s work.

The origins of the word ‘cryptic’ ultimately lead back to the Greek kryptós, meaning hidden or secret. But since its first known usage in the English language in the 17th century, the term seems to have always carried connotations of ‘hidden meaning’ rather than ‘physically hidden’. Common synonyms offered by the Merriam-Webster Thesaurus are: ambiguous, dark, enigmatic, equivocal, obscure, and vague. But the thesaurus cautions that, while all these words mean ‘not clearly understandable’, ‘cryptic’ implies a purposely concealed meaning.

A common type of graffiti seen on roads and footpaths everywhere is made by surveyors who, aided by remote sensing devices, draw maps of the underground with fluoro spray-cans. I am tempted to use the word ‘cryptic’ for this writing because for most passersby like me it is meaningless. But for the government agencies and utility companies who need to know where tunnels, pipes and cables are buried, the survey marks impart important advice. They do not purposely conceal information but deliberately reveal it. They are not cryptic.

There is one more type of graffiti I want to mention that is cryptic. How could I not? The history of the worldwide phenomenon of ‘name’ graffiti that began as New York subway-style ‘writing’ in the 1960s is a history of encryption. Graffiti forms – including the ubiquitous ‘tag’ and the wall-sized ‘pieces’ that use highly stylised calligraphy – encode a graffiti artist’s street name or their ‘crew’ affiliation and make territorial statements. Their meanings are understood only by the cognoscenti.

Libraries of books have been written about these forms of graffiti, but I still like to quote Robert Reisner, an academic graffiti historian from the 1970s. Reisner was not interested in what graffiti looked like. His books were basically compendiums of old-fashioned graffiti transcribed by him and given some sort of sociological or linguistic explanation. He dismissed the “recent phenomenon of the spray-can artist” because its content was “relatively unimportant”.

Reisner had no inkling that ‘name’ graffiti would become international, dominating worldwide public places for decades. He complained that the spray-can art itself had become the message. He was right about that. But he did not understand that the message was meaningful, with the meaning intentionally hidden in the aesthetic possibilities of invented lettering and unconventional spelling.

Images and references

‘After pulling up some old carpet, Camperdown [Sydney, NSW]’, two photos by Vince Righi on VSR Construction Facebook page, 2020.

Phillips, S. A. (2019) The city beneath: a century of Los Angeles graffiti, New Haven and London, Yale University Press.

POW!WOW!HAWAII 10 Year Anniversary, photo on Cryptik web page, 22 February 2020.

Peace on the streets, Vandalog – A Street Art Blog, 16 August 2012

Cowie, T. (2018) The story behind the cryptic drawings appearing on Melbourne footpaths, The Age, Melbourne, 3 December 2018.

Photo Instagram @astral_nadir

Merriam-Webster Thesaurus, ‘cryptic’ synonyms.

Survey marks, Surry Hills, NSW, 2009, photo Megan Hicks.

Reisner, R. (1971) Graffiti: two thousand years of wall writing, New York, Cowles Book Co., Inc.

Reisner, R. & Wechsler, L. (1980) Encyclopedia of graffiti, New York, Galahad Books.

Hicks, M. (2013) Pavement graffiti: an exploration of roads and footways in words and pictures, PhD Thesis, Macquarie University, NSW.

Juxtaposition of carefully explicit and extravagantly cryptic graffiti, Enmore, NSW, 2008, photo Megan Hicks.