There are forms of written communication in the street that speak only to the cognoscenti or the curious. And despite the dominance of e-communication, the disappearance of suburban newspapers and the degradation of postal services, print and handwritten messages still play a role in local conversation.

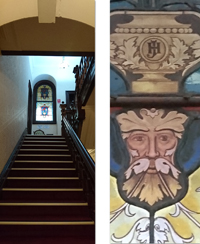

This lovely old post office in an inner suburb of Sydney is a participant in the evolution of communications. Built in 1895, it was decommissioned by Australia Post one hundred years later and replaced by a post office shop down the road. The building deteriorated even after a brother and sister bought it to use as a warehouse for the charity they ran. After those people died it was vacant for many years. Although it is now up for auction it remains in an abandoned state, with windows broken and a metal grille across its front porch.

No letters pass across its heavy wooden counter, no stamps are sold, no mail can be collected from its post boxes. And yet this empty landmark building continues as a centre of communication. Its exterior walls are noticeboards where graffiti tags signal their writers’ transit. Where stickers hint at esoteric secrets. Where posters advertise performers, performances and protests – shredded by rain they are soon replaced by fresh news.

But not all the messages are vertical. On the floor of the gated porch there are always one or two puzzling calls of distress. Handwritten on random pieces of card or paper and carefully slipped under the metal grille, they are almost unnoticeable amongst other windblown detritus and pigeon droppings:

‘help a brokers chosen loser’ in the margins of a local government flyer

‘please help a Canaccord Genuity chosen loser’ on a scrap of paper weighted down with a Thomas the Tank Engine book

‘help a brokers chosen loser’ in a CD case.

I have been photographing this person’s missives for several years now. They seem to be concentrated in the post office entrance these days, but I have also seen them at other spots close by – the lane at the back of the post office, the brick fence of a nearby church, a bus stop just around the corner.

Curiosity finally sent me to Google and I’ve found that the grievances – and perhaps the street notes – date back to 2010 when there was a problem involving a stockbroker and this person’s inheritance. He has a community Facebook page that is ‘about people who always lose over time when attempt to invest thats not to say they have’. But he is the only person that posts and usually the only person who comments on his posts.

In his posts he reveals a great deal of personal information and airs his opinions on stockbrokers, bankers, vets, Christians, atheists, psychiatrists, podiatrists, socialists and vegans, none of whom, apparently, have any sympathy for ‘permanent savings losers’.

It’s interesting then, that with a limitless potential audience on social media, this person still chooses to complement his exposed Facebook identity with anonymous little street notes. Like a graffitist who asserts their presence in a locality with multiple tags, the ‘loser’ permeates the neighbourhood with his anguish. But unlike tags his portable graffiti works do not mark any fixed urban surfaces. Instead he ensures the permanency of his paper messages by constantly replacing them.