4 July 2021

When I began my circumambulation of the Johnstons Creek catchment rim I was prepared for the unexceptional. Unlike last year’s explorations of the creek itself – when I found offbeat backstreets and mini banana jungles – on this series of excursions I expected that only the occasional quirky garden ornament or letterbox would relieve the familiarity of the suburbs I passed through.

To some extent this is turning out to be the case, but on this third excursion I have a moment of revelation, and I also come across very large infrastructure treasure that somehow I had overlooked in all the years I have lived in the inner west of Sydney.

I started where the imaginary catchment line emerges from between two small, pretty and unremarkable brick houses in a style common to this neighbourhood of Stanmore. Nothing much is going on in the street except for an elderly woman taking in some sun on this cold but bright day.

I stand in the middle of the road and look southeast down the slope. From here I can see across to the other side of Stanmore, and beyond that what must be the telecom tower on the opposite ridge in King Street, Newtown. I am surprised to realise I am looking across the valley of Johnstons Creek. This may seem obvious – I am, after all, standing on the catchment rim – but momentarily I understand the topography of the area without the distractions of urbanisation. There is no way I can properly capture what I am seeing in a mobile phone photograph.

I do not walk down the slope, but keep following the ridge as best I can as it winds between houses, across streets, down back lanes. I am getting closer to the less respectable surrounds of Parramatta Road; graffiti and garage-door murals are starting to appear.

Then, beyond the Seventh Day Adventist Church, I spot another surprise. It is the top of a tall, brick sewer vent.

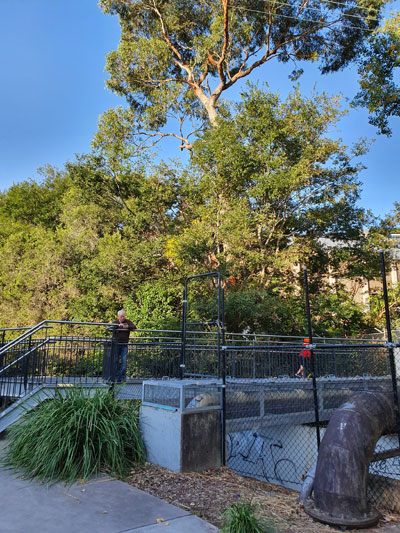

My route takes me through more twists and turns until I come to the entrance of Percival Lane. And there, on the next corner, is the magnificent sewer vent standing in the front yard of a little house. White wisps of condensation float from the chimney into the cold blue sky.

Just half an hour ago I had a flash of insight into this area’s geomorphology. But now I have reverted to admiring the monumental accoutrements of civilisation. Later I will read that this is a ‘classicist late Victorian sewer vent’ with Sydney Water heritage number 4572732.

I have had enough excitement for the day and resolve to resume my walk on an overcast day when I can get photos of the vent and its house without the dappled shadows cast by street trees. I return to the car via a lane beside the Seventh Day Adventist Church, where earlier I noticed a rustic little table in a throwout pile. I will use it as a plant stand in my backyard.