bill bisset is an experimental Canadian poet whose work attracts both praise and controversy. This photo was taken in the carpark at Sydney Park, St Peters (2010).

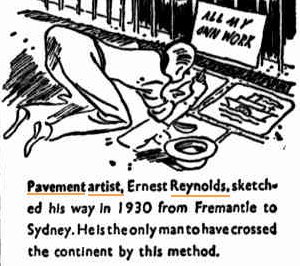

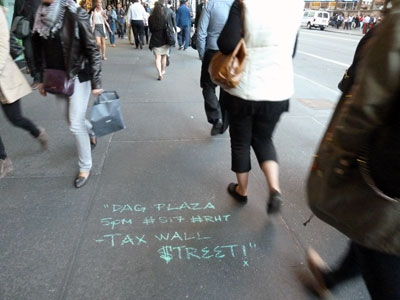

Pavement writers love poets, and poets love pavement writers. A blog about pavement graffiti might seem a prosaic sort of thing to write, but I am in good company. There are plenty of poets who have found inspiration in the marks on the paving. For poets these marks are associated with memories of childhood life, expressions of the inner life, the playing out of private life in public, and the sordidness of life in the gutter.

Today I offer you a selection of some favourite works by Australian poets, and one song. These are only excerpts. (The photos are from my archives)

If we went back to school

everything might seem small.

We could begin again. Pick it up.

Start over. Scribble initials

in a chalky love-heart

on melting asphalt

or something concrete …

Michael Brennan, ‘Postcard’, from The imageless world (2003)

Tar flowers is what grows best in Newtown

Tar Flowers

in concrete gardens

where we draw our best pictures

with bits of tile that fell off Mrs. O’Leary’s toilet roof …

Terry Larsen, ‘Tar flowers’, The Union Recorder (University of Sydney), 2 October 1969, p.49 (1969)

… ETERNITY he’d heard great preachers shout

And shook to hear, but say it he could not.

No, it must come like moonlight or like frost

Silent at night like mushrooms quietly growing

To wake the wicked and redeem the lost;

Like white feather in the dawn wind blowing,

Perfect and white, like copperplate in chalk …

And that was when Arthur Stace began to walk …

Douglas Stewart, ‘Arthur Stace’, (c.1969)

… All writers wait in patience for the chance

to etch their names before the concrete sets

they know that galaxies are speeding further

apart, and faster: that deep space

is overcrowded, that dark matter

spills over into skies …

Gloria B. Yates, ‘Before the concrete sets’, The Mozzie 10 (5), p.12 (2002)

So what I said is what I said

And what you said is what you meant

And when you left my house in the morning

You wrote your message on the cement

You put the letters and the numbers under people’s feet

You took all the dealings and feelings and wrote them on the street …

Megan Washington, ‘Cement’ on album I believe you, liar (2010)

… The boy on drugs, his bandages slipping,

argues and pleads all day with the parking meters.

The filthy children of Christ lie on mattresses in the sun,

the pavement scrawled with graffiti, in excrement and blood …

Dorothy Hewett, ‘Sanctuary’ from Rapunzel in suburbia (1975)