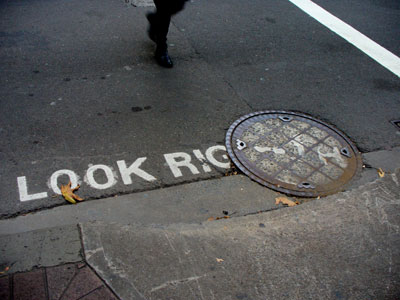

I cannot help liking manhole covers. In fact they feature in quite a few of my blog posts. In October 2010 I wrote: They are reminders that the pavement is not only a floor but a roof – the roof of a busy world of tunnels, tubes, chambers and canals; of light, electricity, water and workers. Manhole covers are shutters on the skylights in this roof.

But why do I persist in calling them manhole covers? I am usually careful about using gender-neutral language, and there are alternative terms available – service cover, access hatch, maintenance hole, for instance.

Although part of the answer is inertia – that’s what I’ve always called them – there is also the desire to align myself with a loose but international oddball fraternity of people who find aesthetic satisfaction in manhole covers. They admire the dull sheen of worn cast iron, remark upon the distinctive municipal manhole embellishments in Japan, take rubbings from old street covers and reproduce them in knitted bedcovers, and photograph tiny weed gardens growing in the patterned indentations.

If ‘manhole’ had not been part of my vocabulary I might have missed Mimi and Robert Selnick’s lovely book of black and white photographs, Manhole Covers. I certainly would not have found one of my all-time favourite websites, Tim Pitman’s Misplaced Manhole Covers. Worse still, people interested in manhole covers would never find my site.

Anyway, does it really matter that we call them manhole covers? It’s an established term in the English language. My copy of the Macquarie Dictionary (Revised edition 1985) defines ‘manhole’ as a hole, usu. with a cover, through which a man may enter a sewer, drain, steam boiler, etc. And there you have it. Why does their name need to be gender inclusive? It’s men who use manholes because it’s men who do the dirty work underground.

That was the entrenched opinion of many people when Andy Mitchell, the chief executive at Thames Tideway Tunnel, recently announced that he wanted to achieve gender parity by the time construction of London’s ‘super sewer’ was finished in 2023. There was a response of disbelief because, after all, this is a distinctly unglamorous construction project in a ‘man’s world’.

Andy Mitchell, chief executive of Thames Tideway Photo: Matthew Joseph/Thames Tideway in The Guardian 10 December 2014.

Browsing around a bit more I found a string on Yahoo! Answers/Social Science/Gender studies in response to the question ‘Why don’t women often choose jobs such as coal miner sewer worker etc. are these jobs unfeminine?’. While most replies were ill-informed, anti-woman and/or anti-feminist rants, there were some interesting thoughts amongst them.

One person wrote that those dirty, dangerous, unhealthy, jobs are called ‘glass cellar’ jobs. Feminists, he maintained, are only concerned with the ‘glass ceiling’, and look to the top in an attempt to shame society into giving women ‘positions of power’. They should also be looking at getting equal positions for women at the bottom. Men choose those jobs because they pay well as a trade-off for safety and comfort.

In reply to others who insisted that women won’t do dirty jobs, one man wrote, “In my former metropolitan area, the Labor Council and many of the individual unions sponsor a program to recruit and train more women for labor jobs. With no exceptions, whenever they open the books, every single available spot is grabbed by a woman looking to get in”.

A couple of years ago, the Daily Mail reported that two young women were to become the first females in Britain to start an apprenticeship in waste. The newspaper’s headline read ‘The pay’s OK but the hours stink’. Looking for an alternative to office work, these women applied for a position with South West Water where their jobs would involve visiting sewerage works, hand-raking raw sewage, taking samples for testing and using rods to clear blockages.

Change, of course, isn’t always easy. A New York Daily News article sub-headed ‘They work in the sewers all day, but they say the really nasty stuff wasn’t in the pipes – it was in the locker rooms’ tells the story of two woman laborers for the city’s Department of Environmental Protection, who have withstood years of threats and insults from male colleagues treating the agency as ‘a man’s world’. The pair claim that they were denied overtime and promotions, and that the few other women in the agency were driven out by constant harassment.

But, as Andy Mitchell continues in the Thames Tideway article, ” From my first day in the job, I knew this was a place where we could achieve something different which would leave a legacy for generations about how good the construction world can be. This is not really a man’s world: we need women, and we need diversity […] We are working to create a culture that finds out from women themselves what they want and how they think we can attract their counterparts. It’s not a bunch of blokes sat around a table making assumptions on why we think women don’t want to work in construction. We are finding out the true obstacles so that we can we try to overcome them”.

Back to manhole covers, then. Baden Eunson tells us that ‘manhole’ is a restricting name that reinforces traditional gender roles. Such terms are examples of the ways in which the English language reinforces patriarchy. Other examples include spotlighting (male nurse, career woman); dimunitivisation (actress, waitress); differential naming (Mr Smith and the girls from Accounting); and featurism (Prime Minister Julia Gillard wore a little black dress and a collarless blazer with olive green sleeves when she gave her farewell speech). Eunson’s article on ‘Gender-neutral communication: how to do it’ was published in a recent issue of The Conversation.

Amongst speakers (or writers) who persist with masculinely-loaded language, some do so because they are openly opposed to all this feminist nonsense and what they think it stands for. As for the rest, some are fuddy-duddies who do not want to put effort into changing old habits. Others do not want to sound conspicuous amongst peers who normally use non-inclusive language. Of course, even amongst these people, I think there are those whose resistance to gender-neutral language is really an indicator of their resistance to gender equality, even if they won’t admit it to themselves.

Where does that leave me and manhole covers? Down amongst the fuddy-duddies, I suppose. Since I intend to go on photographing these enduring items of street furniture, it is up to me to find a term for them that I can use consistently and comfortably – ‘cast iron street covers’, perhaps. But I will probably still include ‘manhole covers’ in the list of tags and keywords for relevant posts, in the needy hope that this will bring some extra hits and likes.

Last resting place for cast iron service covers — Sydney Water’s Movable Heritage Store, Potts Hill (Sydney). Photo: meganix 2015.

Reference

Melnick, Mimi & Robert Melnick, Manhole covers, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1994.