The chalked outline of a corpse is a crime fiction cliché. It is seldom used in real police investigations and yet the image has been assimilated into our everyday visual vocabulary. Advertisers, illustrators and safety authorities have appropriated the familiar shape to encapsulate their warnings about crime and violence. In Sydney’s inner west, young professionals are gradually replacing the students, activists and artists living in what used to be cheap accommodation there. But as I photograph the increasingly upmarket streets of Newtown, I find that graffitists still use its pavements to broadcast their protest messages and sometimes they make their point by filling in the blank forms of body outlines.

(This article was originally published in 2009 the first issue of Second Nature: International journal of creative media, produced by the School of Creative Media at RMIT. It was meant to be the first in a series of essays examining the pavement as a medium of expression. Unfortunately Second Nature did not continue and even that first issue is no longer available on-line.

As a blog post it fails miserably according to WordPress – it has too many long words, long sentences and long paragraphs, too much passive voice, and not enough subheadings. Surprisingly WordPress does not mention that the content is a little dated even though it is. Fortunately I am not trying to sell anything and I hope my literate readers enjoy the post despite these failings.)

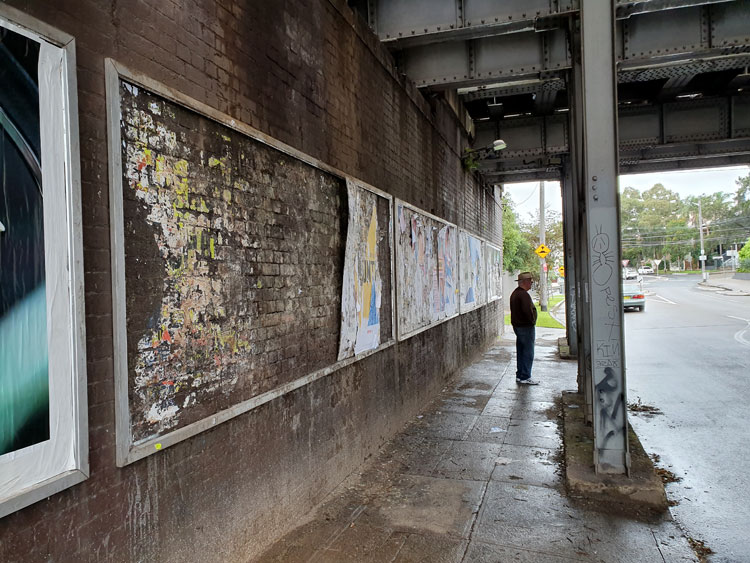

IT LOOKED AS IF THERE HAD BEEN A MASSACRE – the position of several corpses had been marked with outlines on the footpath near the railway station. It wasn’t the first time this sort of thing had happened in the area. I had seen crime-scene outlines on Newtown pavements about fifteen years before. I have seen them intermittently since then and these days I photograph them to preserve some permanent record of their existence. Chalked bodies fade quickly under the assault of passing feet; spray-painted versions last longer, but eventually these disappear as well. Newtown being the sort of place it is, they are inevitably replaced by fresh ones sooner or later.

As it turned out, this latest batch of outlines was evidence of a series of homicides that had happened, not here in Sydney’s inner west, but nearly 1000 km away. Recreated homicides, actually. The drawings were part of an outdoor marketing campaign for the 2008 television series Underbelly – a fictionalized memorial to Melbourne’s 10 year ‘gangland war’.

On the other hand, those first body outlines I had seen in Newtown many years previously were commemorating a different kind of wartime event – the bombing of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. Every year peace activists around the world observe Hiroshima Day by holding rallies, and sometimes they draw bodies on their local pavements. These are supposed to simulate the marks left when people were vapourised by the bomb’s heat blast. Judging from the few photographs taken in Hiroshima that day, the real body shadows were blurred and formless, and yet it is the clichéd homicide silhouette that activists have chosen to use in their peace demonstrations. The outlines make the street look like a crime scene, and for anti-war protesters that is the point.

Newtown has a high rate of metaphorical crime. Body outlines are pressed into service for all sorts of causes.

In peace protests their manifestation is not limited to 6 August. There was, for example, a spray-paint installation that appeared in Goddard Street early in 2003, when Australia joined the war in Iraq. ‘NO WAR’, written in huge letters on the side wall of a café, was accompanied by a slew of life-size figures on the footpath. Their stark remains decorated the asphalt in that tiny side street for several years.

Around the corner, in the main street of Newtown, synthetic bluestone pavers are gradually replacing the asphalt footpaths, just as young professionals in renovated properties are gradually replacing the inner-city students, activists and artists living in what used to be cheap accommodation in the area. But despite the upward mobilization of Newtown, pockets of resistance still exist, from old leftie Bob Gould in his chaotic book arcade at one end of King Street, to young anarchists in crusty flats above the shops at the other. And although the gritty monochrome of old asphalt was more suitable for inscriptions in chalk and paint, protesters still manage to use the footpaths of King Street as a billboard for their messages, defying the unfriendliness of the new pavers’ neatly repetitive grooves and shiny mottled surfaces.

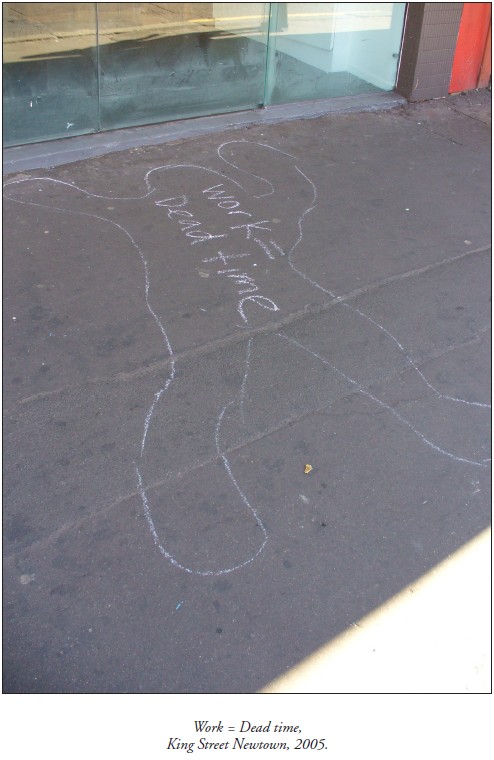

Take, for instance, the trail of crime-scene outlines that I photographed in September 2005. These marked the progress of a mobile street performance by students belonging to an anti-capitalist collective called 30A. Suited ‘capitalists’ had rolled a giant gold coin along the footpath in King Street, mowing down ‘workers’ as they went. Shapes were traced around the ‘victims’ and the space inside the outlines was filled with slogans like ‘Howard kills jobs’, and ‘Work is death’. It was all pre-publicity for a mass protest to be held later that week, not in Newtown, but outside the Forbes Global CEO Conference at Sydney Opera House.

Newtown often acts as outrider for demonstrations happening elsewhere.

This explains another outbreak of body outlines in King Street in February 2004 – it coincided with a riot in Redfern a few kilometres away. Anti-police violence had erupted after Aboriginal teenager TJ Hickey came off his bicycle and was fatally impaled on a metal fence. Redfern locals claimed a police car had been stalking the boy. While the aftershocks of the riot were still happening, crudely chalked bodies appeared on Newtown pavements, accompanied by slogans such as ‘Stop racist police brutality’, ‘Cops kill children’, and ‘To kill an Aboriginal is to kill history’.

The grim form of a hastily circumscribed corpse is a crime fiction cliché. It is a recognizable image that has been appropriated, not only by social agitators, but by graphic artists everywhere who want to allude to crime or violent death in a metaphorical way. The pudgy, larger-than-life human form has become a regular symbol in our visual vocabulary, so familiar that it is available for parody. Newspaper artists exploit the image to illustrate feature articles. Cyber-crime? A chalked body holding a computer mouse. Car theft? The silhouette on the asphalt of a disappeared car. Advertisers have flogged it to death. Telstra MessageBank? A taped outline of a phone left off the hook by ‘flatmates murdering messages’. iiNet broadband? A forensic investigator drawing round a computer thrown to the ground by its frustrated owner.

The murder-scene outline has caught on as a pop-culture motif despite rarely being used in true police investigations. Old Sydney detectives are adamant that they never drew them, if only because the chalk dust would have contaminated evidence. Archival police photos seldom show them. The body outline is largely a construct of fiction thrillers and television dramas, but it has taken on a life of its own.

Its featureless form captures the essence of the human body – the shell that remains after the soul has departed. It evokes the murderous act but lacks the ugly complications of a real corpse. It is an empty space that allows room for the imagination. A thought bubble where the violent event can be visualised. Or a speech balloon that radical students can fill with slogans.

Although homicide detectives do not draw body outlines, police at motor vehicle accidents do, or at least they used to until fairly recently. Hardy crash investigators joke about the ‘gingerbread men’ spreadeagled at the scene of ‘fatals’, but admit that they were distracting to motorists and distressing for passers-by. These days they spray-paint the scene with esoteric patterns of lines and arrows instead.

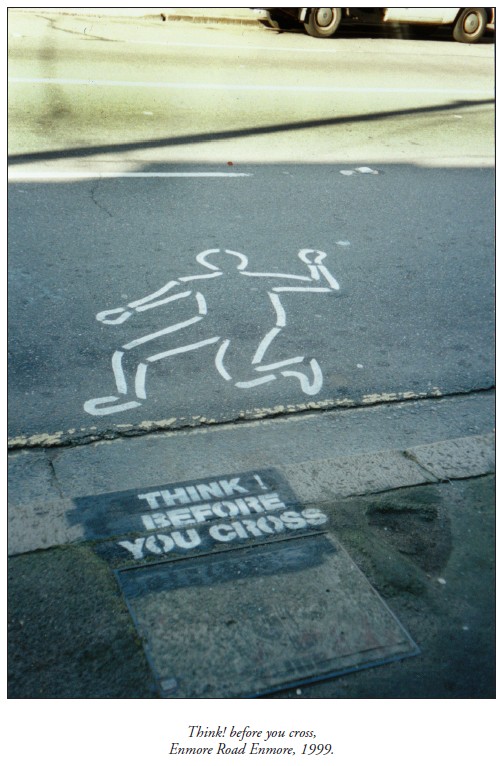

But it was their very potential to distress passers-by that prompted traffic authorities to resurrect body outlines for a series of pedestrian safety campaigns around Sydney in the late 1990s. The aim was to scare reckless road-crossers by stencilling a plague of flattened figures at danger spots on roadways. ‘Step safely’ warned the adjacent pavement signs, ‘Think before you cross’.

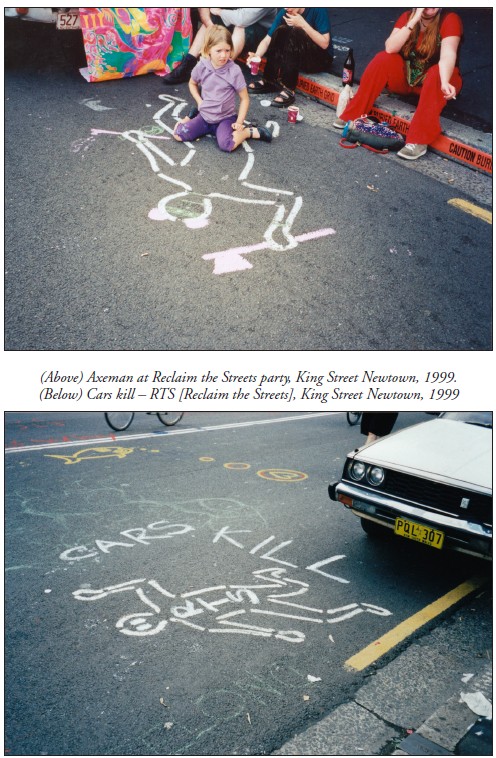

Newtown being the kind of place it is, it was not long before local culture jammers tampered with these spray-painted silhouettes. They were especially active during the annual Reclaim the Streets demonstration in 1999, when King Street was blocked to traffic and rebellious pedestrians commandeered the roadway. Challenging the safety campaign’s insinuation that pedestrians are responsible for road fatalities, RTS activists reanimated the stencilled corpses with painted hair and eyes, with Mickey Mouse ears and tomahawks. And they filled the empty outlines with slogans like ‘Cars kill’.

Sources

Adams, Cecil, ‘Do crime scene investigators really draw a chalk line around the body?’, The Straight Dope, 13 April 2001.

Campbell, Nerida, Curator, Justice and Police Museum, Sydney, pers.comm. 2005.

Gibson, Ross, University of Technology, Sydney, curator of ‘Crime Scene’ installation, Justice and Police Museum, Sydney, 1999-2000, pers.comm. 2005.

iiNet, ‘Don’t take it out on: your computer’, advertising brochure, c.2008.

Jenkins, Peter, Senior Sergeant, NSW Police Crash Investigation Unit, pers.comm. 2005.

Jones, Quentin, photographs for ‘Steal traps’ article by Bob Jennings, Drive, pp.1, 6-7, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 June 2001.

Members of 30a (Annonymous collective of streat theatre bandots [sic]), pers.comm. September 2005.

‘Photographs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki’, Gensuikin.

South Sydney Council, ‘J walking: deadly walking’, Babylon Creative postcard, c.1999.

‘Sydney prepares for Forbes Conference and 30A protest’, Wikinews, 30 August 2005.

Telstra, ‘Stop flatmates murdering messages’, AvantCard postcard, 1999.

Tremain, Cathryn, picture for ‘Catch me if you can’ article by James Hall, Next, p.1, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 March 2003.

‘Underbelly [Uncut]’, DVD, Nine Network, Australia, 2008. Walker, Emily, ‘Shadows of death. Atomic bomb hit Hiroshima 60 years ago’, Kalamazoo Gazette, 7 August 2005.

Original publication

Hicks, Megan, ‘Outlines (Watch this space)’, Second Nature, 1, March 2009.