Ernest Reynolds was a street showman, a colourful character who made a living as a pavement artist for over 30 years. His home town was Adelaide in South Australia and he claimed to have travelled the world as a seaman and artist. On the tramp around country towns in Australia, he drew such crowds that he often rated a mention in local newspapers as ‘the swagman artist’. His career as a ‘pioneer in chalks’ began in Sydney around 1900 and by the 1930s he was setting up his pitch in places like Adelaide, Mount Gambier (SA), Broken Hill (NSW) and Kalgoorlie (WA).

Described by reporters as a ‘picturesque personality’, Mr Reynolds called himself ‘a travelling artist and scientist’ and made pronouncements about scientific matters including, for instance, the geological origins of the Blue Lake in Mount Gambier. In Sydney, he said, he had been decreed the world’s champion pavement artist in 1930, and he liked to be referred to as the King of Pavement Artists.

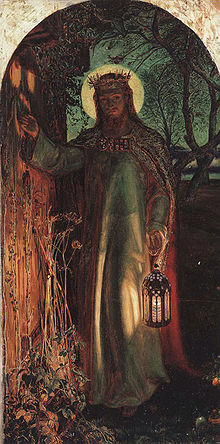

He also told reporters that he was a descendent of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the famous 18th century English painter. But his most famous pavement art work was a rendition of William Holman Hunt’s 1851 religious painting, ‘The Light of the World’, which he could do in 6 hours 18 minutes. Once, after this picture had been on the pavement for several days in Broken Hill, the Barrier Miner newspaper reported that ‘ one devout woman … to prevent its desecration by the feet of the multitude, visited the spot with scrubbing brush and soap and washed the pavement clean’.

The Light of the World (1853–54) is an allegorical painting by William Holman Hunt representing the figure of Jesus preparing to knock on an overgrown and long-unopened door.

Reynolds made amusing comparisons about the generosity of various towns. In Sydney, he said, the people hurry past and ‘let you starve on!’ And in Mount Gambier he told a reporter that the public did not seem to be aware of the fact that he was doing this work for a living. The journalist duly wrote that ‘he would like them to realise that a silver coin would be acceptable’.

The drawing at the top of this blog post is copied from another blog Cipher Mysteries. Blogger Nick Pelling found Ernest Reynolds while hunting down another person named Reynolds (it’s complicated) but does not mention where he found the picture.

But I first encountered Ernest Reynolds in yet another blog, All my own work! – a history of pavement art by Philip Battle. I have since found out more by searching for newspaper articles about Reynolds in the National Library of Australia’s marvellous resource, Trove.

Philip Battle’s stories about screeving – mostly in Britain – are based on meticulous research and his posts feature wonderful archival illustrations. Philip is now turning his blog into a book, and he is hoping to raise a modest sum to publish it through crowd funding. Perhaps you would like to help him.

![Road safety poster using Ian Macmillan’s famous 1969 photograph, issued by the Kolkata [Calcutta] Traffic Police in February 2013.](http://www.meganix.net/pavement/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/BeatlesKolkata_65951375_9358d13f-8536-4294-98c6-2b358c560b1f.jpg)