In my so-called office at home I am attempting to regain control. The room has been overtaken by stuff and progress is slow because I have neglected the fundamental rule: DON’T READ.

Amongst things that I have sinfully paused to read while culling superseded files, I found notes I took at the orientation day for new PhD students in the Division of Society, Culture, Media and Philosophy at Macquarie University in 2008. It was on that day, by the way, that I discovered I was not the oldest PhD student in the world, and that there were many other culmination-of-career candidates. Anyway, here’s one piece of advice I dutifully noted:

At the beginning, keep a journal of what you read and what you think about it. Your notes will be like Ariadne’s thread leading you through the maze. They will help you to solidify your thesis topic or even change your mind about what that might be.

Well, I did start a journal, which became a series of A5 notebooks. The PhD has since been completed but, many volumes later, I still keep this journal, with notes on what I have read, seen, heard, talked about, and thought about. It is quite separate from my daily diary of appointments and humdrum domestic events. As a diversion from room-tidying I hunted out Volume 1 to re-read the first thing I had written in the journal. Here it is (slightly edited):

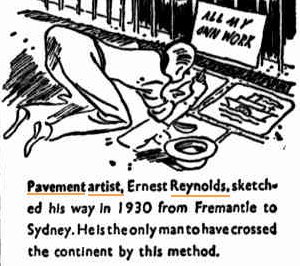

If I am going to do this project I am going to have to re-find my belief in the magical properties of the pavement. These last few years my writing and thinking have become prosaic. I have lost fun and wonder – beaten out of me by [my workplace]. When I first started photographing footpaths eight years ago, suddenly I could write poetry.

Over the next few years I did manage to recapture the magic as I enjoyed the luxury of exploring, photographing, reading, thinking and writing without the need to churn out memos, attend interminable meetings, play office politics, carry the dead weight of work-shy colleagues and endure the hysterics of others, attend to bureaucratic niceties and write formulaic justifications for every decision – and that was in what many (including myself) would have considered a dream job.

Once I left that job, how lovely it was on a nice sunny day to admire the sparkles in the asphalt and concrete, on a nice rainy day to enjoy the wavering reflections of the world on the ground, and on any day to seek out the messages people leave on the pavement and speculate why they leave them. And, in imaginary dialogue with scholars past and present, to discuss both the enchanting and the disheartening aspects of public places, and to consider what’s so special about the pavement.

These days I’m a bit more relaxed about the pavement. I don’t feel I have to look at the ground all the time in case I miss something, but I’m still interested in what’s so special about other places in the urban landscape that are so obvious they’re invisible.